Educational publishers incur more profit than other sectors of the publishing industry due to the nature of the trade: textbooks will always have a high demand. Education publishers have started to utilise digital products in order to increase profits. Software is being developed in formats such as apps to allow additional content to be purchased.  One advantage digital textbooks hold over their physical companions is their capability to automatically update themselves. This prevents publishers from losing money as – rather than having overheads from unsold copies of out-of-date textbooks, or having to pay for pulping – they can work with the authors to alter the original content, ensuring it is up-to-date and current. One prime example of a company adopting this method is Apple – more specifically, their iOS-app called iBooks. If a reader purchases a textbook which is then republished, they will be notified by Apple so that they “can download the updated version free… automatically [replacing] the older copy”. iBooks allows students to highlight specific text and add notes to their textbooks before they “switch to the Notes view to see all [their] notes and highlights instantly organised in one place”. They can also create study cards, which can be shared with fellow students (Apple, n.d.). This creates a new interactive method of learning for readers, attracting a new demographic of ‘digital learners’ – the tech-savvy who prefer reading to be hands-on.

Digital textbook rental also seems to be taking form in the publishing industry. CourseSmart was founded in the US in 2007 (Coursesmart, n.d.) and has since flourished; starting off with just five publishers, the company now has “a total of 30 publishers… on board” (Farrington, 2013). The company only rent textbooks, made extremely accessible – “you can read them on Windows, OSX, Android and iOS”, and students can also read the textbooks offline if no internet connection is available (The Digital Reader, n.d.). Another key factor to CourseSmart’s success is the range of titles available – by offering textbooks from both small and large publishers they have the ability to “[fill] every niche that institutions need to access”. This has resulted in institutions welcoming the service with open arms as they can “secure access to a range of titles for their students”. CourseSmart uses “analytics which allow institutions to monitor how students are engaging with the books”, meaning institutions can check what students have read. The true success of CourseSmart can be seen through their US usage figures: they work with around 1000 campus bookstores; they have 3.3 million users. I would love to compare these numbers to the UK, but m.d. Fionnuala Duggan states that these figures cannot be revealed. However, she assures “that interest was growing both [in the UK] and across the wider EMEA market” (Farrington, 2013).

So how will digital textbooks continue to prosper? With the rise of ePub3 allowing video and audio to be incorporated into eBooks in new, innovative ways, it is simply a waiting game until digital textbook publishers create new-style textbooks that will engage students using an entirely different method. If more and more education publishers get involved with textbook rental services, students could have access to a whole range of textbooks – no matter how niche the subject – almost anywhere, leading to more profit for both the publishers and the rental companies. Despite this clear exponential popularity of digital textbooks, print is most certainly not dead within educational publishing; “students want a combination of both [print and digital]” (Pilkington, 2013), and I, personally, expect to see the two formats in holy matrimony for years to come. Digital has the power to evolve print textbooks.

600 words

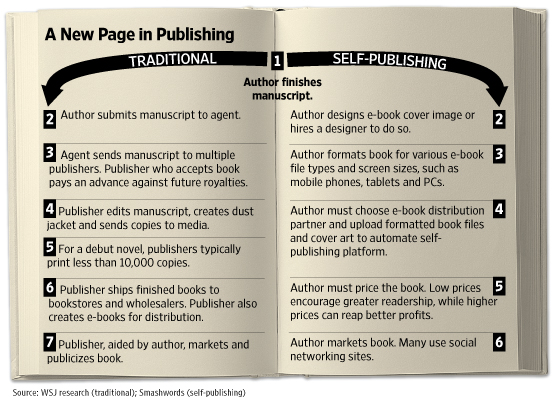

More and more authors seem to have resorted to self-publishing, and with the recent influx of websites allowing you to upload your book in a few simple steps, why not? WHSmith can give us an answer to that; they captured the attention of many readers last month as they shut down their entire ecommerce platform. Their reasoning behind this seemingly-rash decision was the self-published, self-categorised pornographic titles Kobo had on their eBooks feed. The shock was not in the content of the eBooks themselves, but in the fact they were found in the children’s section (McCrudden, 2013).

Amazon and Barnes & Noble have also had issues with twisted erotica on their websites. Both companies “are said to be removing titles deemed inappropriate from their sites” (Rigg, 2013) – maybe slightly more logical than closing their entire eBook store like WHSmith. All three companies “have guidelines prohibiting the publication of offensive texts” (Rigg, 2013) and yet it is obvious that this isn’t stopping some offensive texts making it onto their websites.

So, should more be done to filter what can be self-published? WHSmith are, in fact, “evaluating new procedures to help ensure that this type of content will not become available… in the future”. The site was temporarily offline until they were “totally sure that there [were] no offending titles available” (BBC, 2013). However, this was a reaction to the ‘unacceptable’ titles, rather than an action: essentially, the content should never have been available in the first place. McCrudden (2013) suggests a feedback method where authors are rated by customers; good behaviour rewards them with a ‘top-rated seller’ tag, whereas bad behaviour leads to penalties, such as their work being taken down off the website. This would, however, still be a reaction to works already published onto self-publishing websites. One method that would allow unacceptable content to be censored before publication would be an approval system. However, such systems are currently underdeveloped: with the sheer amount of self-published titles constantly being uploaded, it is inevitable that one or two inappropriate titles will still slip through the net.

As with most things in life, self-publishing isn’t all that bad. After nearly a decade of unsuccessfully trying to persuade a New York publisher to print one of her books, Karen McQuestion decided to self-publish. Eleven months and 36000 eBook sales later, McQuestion most likely has no regrets about using Amazon.com’s self-publishing service. Amazon created an imprint in 2009 – Amazon Encore – in which they publish successful books in print – including McQuestion’s first novel, “A Scattered Life” (Fowler and Trachtenberg, 2010). This shows self-publishing does hold some benefits for authors – and readers who, otherwise, would not have read the book – as it provides a ‘last resort’ for authors who have been rejected elsewhere.

In conclusion, it is clear that self-publishing can have immeasurably great effects for authors, and for companies who offer a self-publishing service. However, a clear divide seems to have been created between self-publishing and ‘traditional’ publishing. So how does this affect the future of publishing? If companies such as Amazon are being given “new power” in the book market (Fowler and Trachtenberg, 2010), it could lead to ‘traditional’ eBook publishers losing out on sales, therefore lessening their profit. Alternatively, publishers might jump on the bandwagon and start offering their own self-publishing services, allowing them to milk as much money out of successful, self-published authors as possible. It’s uncertain how much of an effect self-publishing will have on the big publishers; I am certain, however, that any publishing company who offers a self-publishing service will have to create new methods of censorship over content.

The rise in digital book copies over the last few years has given publishers cause for concern: worries have started to arise over rights-related issues such as piracy. It is due to this that digital rights management (DRM) came about; DRM is “a class of technologies that allow rights owners to set and enforce terms by which people use their intellectual property” (BBC, 2007), and it has caused much debate within the publishing industry.

On the surface, DRM sounds great; eBook publishers can maintain control over how their eBooks are being utilised by consumers, ensuring no illegal copies of the text are made and shared. However, DRM “prevents [readers] from using legitimately-purchased eBooks in perfectly legal ways, like moving them from one kind of eReader to another” (Tor, 2012). This means that readers are buying eBooks but not actually owning them.

As DRM results in customers effectively ‘renting’ the books that they pay for, many issues have cropped up. One such case that emerged somewhat ironically was the disappearing Orwell eBooks in 2009: readers who had purchased certain eBooks for their Kindle, including Orwell’s 1984, found that their copy had been plucked from their Kindle and replaced with a gift voucher amounting to the eBook’s value (Johnson, 2009). Amazon.com seemed to be playing Big Brother, issuing censorship by invading customers’ devices, deleting their content. So what was the reason behind this decision? “The books were added to the Kindle store by a company that did not have the rights to them”, therefore Amazon removed the illegal copies from both their systems and the customers’ devices (Stone, 2009). Amazon is renowned for being a company all-too eager to please its publishers; their decision meant Houghton Mifflin Harcourt managed to recover the rights to the books, so at least someone came out smiling. Essentially, DRM seems to be good for publishers but bad for readers; readers buy a license to the eBook, and not the eBook itself. Frustration can already be seen, as customers “can’t lend people books and [they] can’t sell books that [they’ve] already read” (Woodward, 2013: 16), again emphasising the idea that we never really own eBooks from companies enforcing DRM.

There are numerous ways to get around DRM. One method is through apps such as Calibre; Calibre is “a corresponding plugin that cracks Amazon’s DRM encryption” (Farivar, 2012) so that you can convert it to any desired format, thus meaning you can use any device to read the eBook. This sparks the question: if it’s so easy to get around DRM, is it really worth the hassle? One way to find the answer is by looking at companies who once had DRM-protected eBooks, but now do not. Tor Books removed their DRM-protected content in April 2012, and a year later state that they have seen “no discernable increase in piracy on any of [their] titles”. Customer satisfaction since their decision to remove DRM seems to have increased too (Geuss, 2013), inferring that DRM is, overall, more of a hindrance.

So what is the future for DRM within publishing? A trend seems to have started amongst companies to remove DRM from their eBooks, suggesting that perhaps there isn’t a future for DRM. However, some publishers may still want the comfort of a rights-buffer for their eBooks, despite the numerous methods of jumping over any hurdles it may cause readers. Maybe if publishers fine-tune what is ‘rights’ management, and what is ‘wrong’ management, DRM can make its comeback with a vengeance: as for now, there appears to be too many companies enforcing DRM who take it that step too far.

The importance of an effective digital publishing business model increases exponentially. Recently, an abundance of new business models have been introduced by publishers; this article will be focusing on the subscription model within digital publishing.

A company to have launched recently is Oyster, an American “eReading startup that offers consumers an all-you-can-read eBook subscription model for $9.95 a month”. After just over a week, “the company had reached a million pages read”. Oyster offer titles – including backlist – from companies such as HarperCollins and Houghton Mifflin (Reid, 2013: a). At its launch, readers could only access Oyster’s supply of books through an iPhone; on 16th October 2013 they released an iPad version and “[opened] the service to public download with the offer of a free 30-day trial period” (Reid, 2013: b). For the styling, Van Lancker – one of Oyster’s founders – said the company desired a “’clutter-free mobile reading’ interface”. The text scrolls down as the reader is reading the book, but the app “still offers paging and a progress bar to show how far along the reader is.” Readers can select themes; each theme has a complementary typeface, background colour, and textures. Oyster also ensures text can be enlarged easily so as to improve readability (Reid, 2013: a).

A second company exploring the subscription model is eReatah. eReatah is a new web- and app-based service “offering eBook subscription access to a broad database of eBooks of every genre”. It is available to all iOS and Android devices; content can also be “side loaded into the Kindle Fire, Nook and Kobo tablets” (Rhomberg, 2013). Readers can access their downloaded eBooks on up to six different devices (Digital Book World, 2013). They plan to offer access to “more than 80000 digital titles from major publishers”, including their backlists, “at prices said to be 20% to 40% lower than retail”. Readers can choose from three subscription plans: - Two eBooks per month: $16.99

- Three eBooks per month: $25.50

- Four eBooks per month: $33.50

(Publishers Weekly, 2013: a) So how do the two compare from a publisher’s perspective? The most obvious difference is the fact that Oyster offers an unlimited number of books for $9.99 a month, whereas eReatah limit how many books consumers can read. Oyster has chosen a price point low enough for readers to take them seriously; one effect of this is that publishers, under this model, will make less money. This goes some way in explaining the reluctance from the other big-five trade publishers to uptake the service. However, if consumers are willing to pay more for the service, additional publishers may engage with Oyster. This is partly because Oyster focus on backlist titles rather than recent bestsellers, which would appeal more to publishers economically (Rhomberg, 2013; Publishing Technology, 2013). Comparatively, there is an obvious benefit to publishers using eReatah’s usage-based payment model as publishers “[receive] payment for what people read, every time something is read through the service” (Publishers Weekly, 2013: b). This allows publishers a certain security that they will receive a reasonable profit by utilising the service.

Overall, it is clear the subscription model is developing slowly within the publishing industry. Publishers are still unsure as to whether they will benefit or not – and to what degree. In the future, I believe there will be more services like Oyster and eReatah, and that more publishers will be accepting of such services. Perhaps Oyster will raise their monthly price slightly so as to allow more ease-of-mind to publishers. I also hope for the launch of more companies similar to eReatah – but with more accessibility. We’re not all Apple-mad, after all.

The way we read seems ever-changing: new, emerging technologies appear constantly that revolutionise the publishing world. One recent development is the use of Augmented Reality (AR) to create interactive stories and learning tools for children. Using devices such as iPads or Android devices, AR “allows users to access [relevant information], overlaying layers of digital information to the physical space [whilst]… allowing the interaction with those digital elements as if they actually belonged to the real scene” (AR-media, n.d.). The desire for AR seemed to develop in 2012, and it soon became the year’s “buzz word” worldwide on the topic of games and toys (Raugust, 2012). So, how can publishers utilise AR to create an enhanced reading experience, with both print and digital combined?

Some publishing companies are already combining physical and digital; School Zone predominantly sells eBooks and apps, but also offers free downloads alongside their physical books and flash cards in order to add something extra. To ensure these “tie-ins” will sell they first use focus groups, showing there is an obvious market for a combination of physical and digital (School Zone, n.d.). All publishers need is to take the leap from separate digital and physical content that is brought together, to digital and physical content that is intertwined from the very first stage: AR.

One company that has started to use AR is EDUTOOLapps: using Hands-on Virtual Reality (HOVr) to create a visual experience to aid children’s reading and learning, they combine physical and digital content in one fluid movement. With a range of books on various topics – a list can be seen in their catalogue http://issuu.com/edutoolapps/docs/hovr_2013_catalogue/10?e=0 – EDUTOOLapps are using AR to digitally increase the amount of information given by any one of their physical books. This may be through the use of virtual pop-up diagrams or animations that relate to the information given in the physical book. An example of how EDUTOOLapps use AR can be seen in the video below:

One specific book that demonstrates AR is Horrible Hauntings: An Augmented Reality Collection of Ghosts and Ghouls by Shirin Bridges. Published by Goosebottom Books, Horrible Hauntings is a book of ghost stories that gives the reader that little bit more. As each ghost story is read, the reader can hold an iPad, iPod or Android device so that it is pointed at the picture on the double page spread. Once they have done this, a virtual pop-up appears on the device that illustrates the ghost story. Furthermore, the reader can actually interact with the screen, using their finger to move objects around the room, or blowing at a ghost ship using the microphone. Although aimed at children, the book has received an enthusiastic response from adults too (Werris, 2012). Jason Yim – president and executive creative director of Trigger Global – worked in collaboration with Bridges and believes “augmented reality provides a unique experience that lies at the intersection between [printed books and smart phones and devices]” (Werris, 2012). The trailer for Horrible Hauntings can be found below:

Currently, there is an emphasis on AR within children’s publishing. Hopefully, more publishers will see the successes of AR and integrate them into their own products in some capacity. I would like to see a future where both adults and children’s books use this technology to create a dynamic method of reading: descriptions of characters in fiction accompanied by visual representations; virtual pop-up diagrams for university medicine students; learning a language by reading foreign words in a book whilst they are being read aloud. The possibilities for AR are endless – and I can’t wait for publishers to realise this.

Once upon a time digital products were sacred: your Nokia was fascinating and you would brag about the ability to play Snake on your mobile phone. You would never give your digital products to children in fear of them breaking it or dropping it down the toilet. Now, however, advancements in the digital world have led to an abundance of technology suitable for young children.

More specific to publishing, there has been a boom in digital alternatives to children and YA’s reading experience. Sales of children’s eBooks nearly tripled over the first six months of 2012, up by 171% (Williams, 2012), when compared to the first six months of 2011 (Hall, 2012). This shows a rise in popularity, therefore trust, in children’s digital reading.

So how is the publishing industry keeping up with the demand for digital children’s books? Having recently visited Frankfurt Book Fair 2013, I noticed an emphasis on digital, especially in the section of UK children and YA publishers. Bloomsbury, for instance, have a new digital-first imprint – Bloomsbury Spark – dedicated to publishing a wide array of fiction eBooks for YA and New Adult readers. Offering a vast range of popular genres, Bloomsbury Spark launches in December 2013 and will have new titles monthly, available to purchase wherever eBooks are sold (Bloomsbury, n.d.). Bloomsbury Spark authors already have an accumulative digital fan base of 16000 Twitter followers, more than 3000 likes on Facebook, 20 blogs that total over 10300 views monthly, 3160 Goodreads followers and numerous accounts on Pinterest, YouTube, Google+, and more (Bloomsbury Spark [leaflet]). This shows an evident desire for the digital reading experience, aimed at children and young adults, in an entirely digital-first format.

Bloomsbury is also using the social network hype to their marketing advantage. A Facebook page promoting the soon-to-be-released imprint – https://www.facebook.com/BloomsburySpark – is sure to engage some of the 1.26 billion Facebook users (Smith, 2013); some of these users will be Bloomsbury’s target demographic. Considering it is still yet to be officially launched, they have already gathered up an impressive 227 likes (as of 15:20pm, 27/10/13) that is sure to grow dramatically after reviews and recommendations from readers and companies alike. This is important for Bloomsbury as it allows recognition of Bloomsbury Spark to grow exponentially, essentially turning the imprint into a well-known subdivision of Bloomsbury. “For eBooks that reach a certain level of success, [Bloomsbury] will make them available in print editions” (Bloomsbury, nd). By allowing authors to first gain recognition and a fan base before publishers engage in the production process of creating a physical book, Bloomsbury can be sure that there will be a demand for the end product. This reduces the risk factors involved in publishing physical books – especially with new, previously unheard of authors – as there shouldn’t be as many books destroyed, or sat in storage paid for by the publisher. The production of physical Bloomsbury Spark books will also allow other sales possibilities such as box sets, which could be tied in with Christmas sales to increase revenue.So why are imprints such as Bloomsbury Spark important developments within the publishing industry? In my opinion, the answer to this is the simple fact that it allows the industry to keep up-to-date in this digital age. There is a new demographic: the digital readers – of which you yourself are part of, simply by reading this article. The advancements in children’s digital publishing offer multiple opportunities for publishers and readers alike. There is also hope for a strong connection between digital and print books in the future, meaning they work hand-in-hand to increase sales and turn authors into brands.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed